On August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution became law and American women were finally guaranteed the universal right to vote. This landmark Amendment was the conclusion to a decades-long battle for suffrage waged in states and localities across the country. Before this, some notable initial successes in the suffrage movement took place in the rapidly developing West. The Wyoming Territory had guaranteed women the right to vote as early as 1869 and its leaders would only agree to join the Union on the condition that women would still be allowed the vote. Wyoming was admitted into the Union in 1890, making it the first state to guarantee this right. In November 1893, Colorado joined with its neighbors Wyoming and Utah in granting suffrage to women. Colorado was the first state to enfranchise women by popular referendum. Although the greater national movement was gathering steam due to high-profile activists such as Susan B. Anthony and the National American Woman Suffrage Association, female suffrage remained the rare exception rather than the rule in the US.

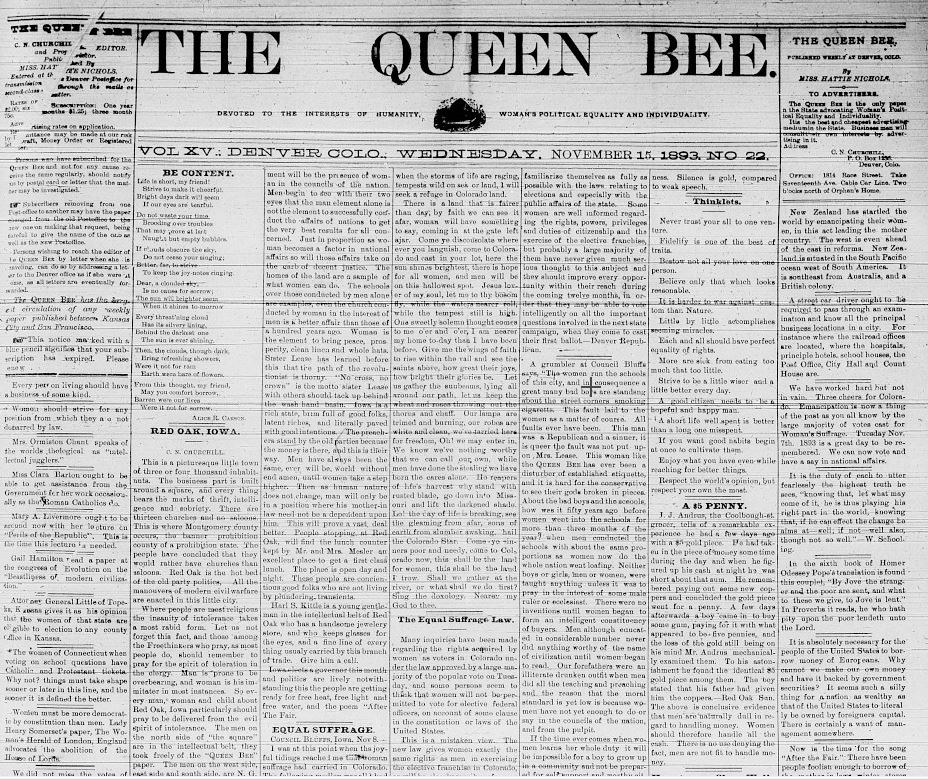

In this Window to History, we are spotlighting the struggle for women’s rights through two titles found in the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (CHNC): The Colorado Antelope (October 1, 1897 – June 15, 1882) and its continuation under a different name The Queen Bee (July 5, 1882 – approx. January 1, 1915 available). The owner/editor was Caroline Nichols Churchill (1833-1926), a feminist, suffragist, and journalist who hailed from Canada but settled in Colorado in 1879, becoming a significant influence on Colorado’s road to women’s suffrage. As our short biography shows, Churchill was a force of nature, writing prolifically about the iniquities between genders and championing equality in a frank and outspoken manner that made her all but unique for the time. Her commitment to equality sometimes extended beyond the genders to ethnic minorities in an age of widespread prejudice against Chinese immigrants and Native Americans, but as we’ll see, Churchill was not immune from her own bigotry and biases.

The first edition of The Colorado Antelope is worth quoting at length as it shows Churchill’s approach to journalism. It is sometimes dense, hard to understand, but packed with nuance, dry humor, scathing sarcasm, and firm opinions. Like all journalists of the day, she wasn’t exactly brief, but unlike most other journalists she was a woman and rarer still a woman journalist who was vocal about her revulsion for the status quo, one where the accepted norm was that womankind was inferior to men in practically every way. With delicious sarcasm, Churchill explains why her newspaper should be a thing:

From a decent respect for the opinions of mankind it becomes our duty to explain how we came to be a woman and we desire to publish a paper. We will reply to these questions by asking others, that is, “How some of the other sex came to be men, and still more mysterious how they ever became publishers of newspapers?” This is a secret which we must leave to Him who keeps in a safe of many compartments the secrets of the universe; the combination of some of those compartments we have yet to learn. It is our opinion that every State in the Union should have a live feminine paper published at the Capital and that such paper should be liberally sustained. As the acquisition of women to the educational department has raised the standard of education and general cultivation, so the acquisition of women to the journalistic department will advance the standard of journalism. It is not good for man to be alone in journalism any more than in any other enterprise. It is not best to always have our oysters served upon the half shell. Woman was given to man as a civilizer. The very fact that she commenced by cleansing his linen proves this assertion to be correct, for is not clean linen a civilizer? Now that the Great Wisdom has sent China men to help us we should look out more advanced work which shall be a civilizer, for man cannot be too much civilized, provided he gets plenty of fresh air.

Ending the column, you can almost visualize Churchill’s pen furiously scribbling, the power of her prose in full flow:

We have lived in this world and arrived at the years of maturity without the protection of a father, he always blamed us for being feminine; we have lived through girlhood without the protection of brothers, they always blamed us for being a girl; we lived a reasonable length of time a married woman without the protection of a husband, he always blamed us for being a strong-minded woman; weak-minded women never need protection because they keep the beaten track. We lived without the protection of law, it also reflected upon our sex. Thus we have been left to do our own thinking and our own fighting and have become developed, and are working out our own salvation; but we have had the protection of the common sense and better judgment of every worthy individual in the community where we have chanced to live or tarry, and it is upon this hope that we base our prospects for success in the future, and we only ask your favor as we find grace in the eyes of your better judgment.

The next edition clues us in on the name of the paper:

Some one wants to know why we call our paper the Antelope. We have several reasons, which shall be given as we “rise to explain.” In the first place, we wanted a name never before given to any paper under the sun; we wanted something that had the least feminine suggestion, something graceful and beautiful, and above all something that was alive and had some “git up” to it. […] There is another reason for calling our paper the Antelope which we will give, but modestly, blushingly, informing our readers of this last best cause least understood: the Antelope is a little deer, and is so difficult to overtake.

This might lead a potential subscriber to wonder about an important point, one which Churchill herself is eager to expand upon:

ADVANTAGES WHICH THE ANTELOPE HAS OVER OTHER PAPERS.

[…]

It has the only lady editor who wears a seven by nine boot and dares tell her own age.

It has the only lady editor who dares so far defy the underlying principles of political subjection as to write and publish a joke perpetrated upon herself.

It is the only paper in the United States giving its opinion earnestly and frankly and with tearful pathos, upon paper, and that will vacillate half a dozen directions in a second for the sake of selling a paper.

[…] it is the most original paper published in the United States, has the most original name and original resources, that it is the wittiest, spiciest, most radical little sheet published in the United States, printed upon handsome tinted paper in large clear type.

The only thing which the Antelope borrows from other journals is its overwhelming modesty.

The Antelope is the only paper published in the United States that is not at all egotistical. Subscribe for the Antelope.

Spend some time with the Antelope and you’ll see that its construction was somewhat haphazard (which is by no means uncommon for the period), with stories that are without titles, or columns that are more like anecdotes or jokes – only the punchline is a little lost on us today. Some of the columns read like excerpts from Churchill’s own diary and seem little concerned with news. The overarching impetus behind the publication becomes clear: Churchill knows what she wants to say, and her confident voice comes through stronger and stronger.

Churchill’s frank writings alienated her from the greater suffragist movement, partly because of the “strong” language she used in railing against bigotry in her writings, and not shying from naming people who fit into that category. Now they seem like rather hilarious takedowns, but it was extraordinary for the time. For example, Churchill travelled extensively and used her paper to chronicle her encounters. Take the strange article ‘What Our Editor Encounters in Transacting Business for The “Antelope,” written in her customary third person:

One of the most shameful phases of our civilization is the prevailing idea that woman cannot travel and transact business as men do, or that she must have an owner before she is as an individual entitled to the least degree of protection. This state of affairs will ever remain until she is in possession of sufficient political power to protect her especial interests as any other class must do.

When at Leadviile [sic] Our Editor hired a room at Dickey’s bakery upon Sixth street. She found Mrs. Dickey a woman of good common sense, a person of some appreciation of refinement, or at least general decency. Her man, Dickey, the legal head of the house, was a different institution altogether; his manner was that of a low-bred horse fancier. He swore like a pirate in the presence of his wife and little daughters, and expected them with their female friends to tremble in his majestic presence. Our Editor has observed almost exactly this human combination of greatness many times before and anticipated what might be expected from this source – a brainless, conceited, bigoted tyrant, with no better acquirements of which to be proud than that of his animal manhood, which simply means sex. In short, a barbarian, an overbearing fool, who is constantly saying by his conversation and manner, “See how great a thing it is to be a man.”

This is quite a long article, so to skip ahead. Mr. Dickey starts to give Caroline Churchill the cold shoulder – and “Our Editor” (i.e., Churchill) is not too pleased by that, and does the same in return. A conspiracy, we are told, is then enacted against her:

Our editor then took it into her head not to notice the Ass. This of all things to a vain, brainless man is most unbearable, so he mediated revenge. He said in his heart, ‘This woman is an interloper; she is found here without an owner; and do not the laws of custom require that woman shall have a master, some one for whom she is working besides herself; and if she has not a legal master is not she obliged to so far conform to public opinion as to select an illegal master known as a friend or protector? Now, I being at the head of this family where this woman has rented a room claim this right, and by the holy hocus pocus, and all the other gods this side of my brick oven, this right shall be respected or I shall know the reason why.’

Churchill lapses into a long scene where (she imagines) Dickey explains to his staff how he and his “fellow barbarians,” “must assert ourselves, must vindicate ourselves” by resolving to “fumigate” Churchill’s room.

So the manly beast who is to begin this grand scheme of fumigating Our Editor gets in a room adjoining and commences to smoke and blow the vilest of the variety of smokes into her sleeping apartment. […] The long, weary night drags slowly away and Our Editor has abundant opportunity to reflect upon the situation. So often has this beastly method of persecution been resorted to in her traveling experience that the first smell of a cigar at night will so alarm her as to start a profuse perspiration and sometimes violent beating of the heart followed by nausea and not unfrequently vomiting. […] Our Editor must go forth in the morning pale from want of sleep, trembling from the effects of a vile narcotic taken in by the way of the lungs and skin, and all her chances of business success lessened for the day, aside from the feeling of being wronged outrageously by the very class who assume to give women protection, knowing that their protection is often more dangerous than their downright displeasure. […] There are thousands of men of the Dickey type throughout the land, thousands of women who would not take the last trouble or pains to protect a sister-woman for fear of offending the master, and, in fact, who take quiet pleasure in knowing that other women are subject to humiliations from the masters. One servant is often pleased to witness the humiliation of another, and the more abject their condition the less will they sustain one another. This is the history of slavery from the beginning of the institution.

If you’ve made it this far, then bravo! As you can see, we’ve not touched on the continuation of the Antelope, The Queen Bee. We’ll let you do your own discovering of the 604 issues we have of this title in the CHNC. But let’s end with one article of note around the time that Colorado’s electorate voted for women’s suffrage.

Council Bluffs, Iow. Nov 8.

I was at this point when the joyful tidings reached me suffrage had carried in Colorado. […] Ring the stage horn, blow the cow bell, that the waiting world may know woman suffrage carried in the state of Colorado!! […] I feel like singing all the time, my tears are wiped away, for I am a citizen now; I’ll sing it everyday when the storms of life are raging, tempests wild on sea or land, I will seek a refuge in Colorado land. […]

In Caroline Nichols Churchill’s journalism we encounter a living voice that orders you to fight injustice and not remain silent in its presence, but also a complicated historical figure who cannot be easily put into a box. Often contradictory, it’s tempting to portray her simply as a progressive, but that would betray her own words. For example, in one article she might champion the humanity of Native Americans, in another she calls for their execution. Churchill’s journalism is imbued with a humor that makes her present, but it can also be extremely cruel and dogmatic. It commands us to be courageous in the face of bigotry, but it often seems little aware of its own bigotry. Without excusing this bigotry, it is an unavoidable fact that she was a product of her time, as we all are. She is a reminder, then, that we can be biased in one moment and rail against injustice the next, we can be antiracist one moment and racist in the next. Perhaps she can be a lesson to us to be continually on the lookout for our own bigotry, and when fighting one sort of bigotry, to be careful not to indulge in another. Yet, her influence is unquestionable – The Queen Bee and its editor were famous in their day and Churchill’s writings likely had an effect on Colorado law and the greater battle for equal rights for women.

- Book Club Author Suggestion: Julia Alvarez - March 18, 2025

- 20 Popular Book Club Sets - January 27, 2025

- Accessibility Quick Tip: What is Universal Design and how does it relate to accessibility? - December 10, 2024