The Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (CHNC) recently reached 3 million digitized pages! The collection contains a breathtaking amount of news that is invaluable to anyone interested in knowing more about Colorado’s history – completely free of charge. There has never been a better time to perform local research with the aid of contemporaneous newspapers, such as The Rocky Mountain News (RMN includes a Daily, and Weekly which goes all the way back to 1859, before Colorado was recognized as a state.) Find out more about the ongoing digitization of the Rocky.

In this article, we will see how the RMN reported on one of the worst moments of racial violence in Colorado’s history.

The Rocky Mountain News covered local and international news and was the longest running Colorado newspaper. It was (at least in 1880) also a clearly partisan newspaper, taking opposition to the Republican party of the day, seemingly at any opportunity.

This point is important, because from the very earliest reporting we see how violence towards the Chinese immigrant community in Denver was spun first and foremost as a failure of Republican law and order, with little regard given to the fact it was likely a few racist individuals, and then a racist mob, that perpetrated the violence, which included a murder.

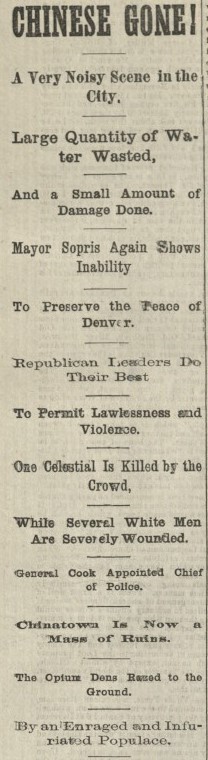

Take the headlines depicted on the left, which blames Republican officials for the noise and wasted water, noting that a “Small Amount of Damage Done,” before mentioning that “One Celestial” (emphasizing the foreignness of Chinese people) was killed, “While Several White Men Are Severely Wounded,” and that, although the damage was somehow small, “Chinatown Is Now a Mass of Ruins.” The reporting that follows is just as concerned by political mud throwing, and just as minimizing of the violence perpetrated on the Chinese immigrant population.

The “Chinese question”

Chinese people had been immigrating to the US in small numbers since the early parts of the 1800s, and widespread anti-Chinese sentiment began building in the US since around the Gold Rush in the mid-19th century when something like 40,000 new migrants entered. The US government and business leaders, however, recognized the huge potential for profiting that this demographic offered in terms of low-cost labor for mining, railway building, and agriculture. Influencers who opposed the migrant workers appealed to white working men by instilling fear of losing their livelihood to a hated other, a sentiment often entertained or encouraged by the press.

The news during this period in the CHNC makes frequent mention of the “Chinese question,” or sometimes more directly the “Chinese problem,” but few journals took the time to actually define these, leaving it up to the reader to infer what is being talked about. What is this question/problem exactly? Everyone at the time seemed to be quite well aware of what this meant, hence little explanation was needed.

In fact, such “questions” about whole groups of people were quite commonly discussed and used as a common strategy to dehumanize minority groups. From a contemporary perspective, this phrasing immediately calls to mind the so-called “negro question,” which had a long history in the US, and it is worth noting that Nazi Germany took inspiration from the US’ treatment of Black people when they propagandized the so-called “Jewish question,” culminating in the mass murder of Jewish people during World War II. The phrase itself always suggested that there was a problem that must be dealt with, giving the questioning of a people’s very existence an air of intellectuality. It was no different when it came to the Chinese immigrant population living through the Reconstruction era (the latter part of the 19th century) in the USA. The general “question” amounts to the same thing: how much should we tolerate the “other”? Or, more specifically, what shall we (the dominant majority of people, supposedly of the same race and mindset, who have the sole right to the land) do with [minority group] (whose very existence in our land is shown to be problematic by my asking)?”

Before there was clickbait

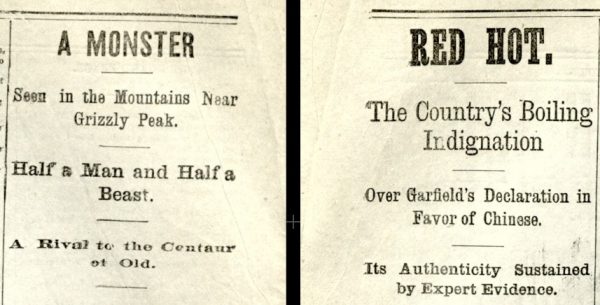

The November 1, 1880 edition of The Rocky was presumably in the final stages of preparations before printing, as the violence in Chinatown happened throughout Halloween day, and into the night and morning of November 1. Above are the headlines of two rather eye-catching stories, which come before the “Chinese Gone!” article that details the violence (perhaps because it was a last minute addition to the edition before being printed the same day, the reporting that is the focus of this post ended up on the final page). Speculation about the sighting of “a monster” took precedence in this edition though, albeit with the following disclaimer:

Several explanations already offered are too mildly improbable for even a moment’s consideration, and as yet this sea-serpent of the mountains remains enveloped in mystery. It is said that a hunting party will be organized to endeavor to run the beast down.

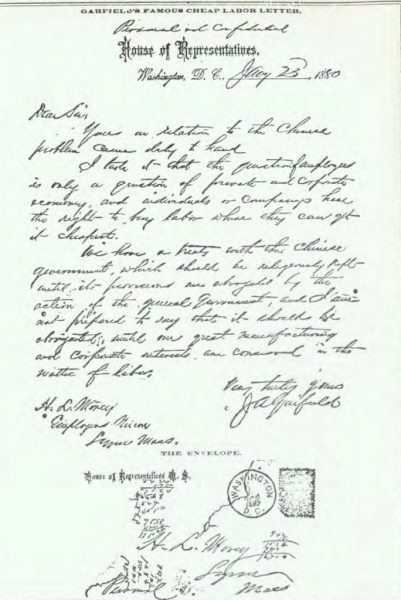

It is easy to say that journalistic standards in general were quite different back then, but even so, RMN was clearly not a paper to let facts get in the way of an eye-catching headline. “Garfield’s Declaration in Favor of Chinese” refers to the Morey letter, purportedly written by James A Garfield in which the president was supposed to have shown support for yet more Chinese immigration, an extremely divisive topic on the eve of the 1880 election and no doubt one of the driving forces behind the anger towards Denver’s Chinese population. Although the letter was rather suspicious when it first appeared and was soon realized to be a forgery, the RMN remained insistent even in this edition that it was authentic, illustrating the overarching style of the paper – one far more occupied with political editorializing than just relaying news. It wasn’t until January 6, 1881 that the paper conceded that the letter was forged.

How was the news reported?

What actually happened on that Halloween? RMN’s November 1, 1880 article offers a timeline of events, beginning with the dispute that started the violence:

Between one and two o’clock yesterday afternoon an American and a Chinaman met in a saloon on Wazee street. The Chinaman had washed some clothes for the American, and there was a dispute between them as to the recompense for the said work. The Chinaman wanted ten cents more than the American was willing to give. This led to a row, rough things were said on both sides, and finally the Chinaman drew a knife and cut the American in the cheek, making a fearful gash on his face. The wounded man ran out showing the effect of his wound, and very soon a number of passers-by surrounded him, and among them two gentlemen from the Planters’ house. The Chinese then fired upon the small crowd, and then the people began to congregate from all parts of the city, and very soon there was a large crowd. It increased rapidly. No Chinaman had been hurt. The streets were full of sight-seers, but no harm had yet been done. About this time the mayor arrived, nearly an hour after the first trouble occurred, Sheriff Spangler arriving shortly before him. Somebody then ordered an alarm to be sounded.

The mayor stated at his office last night that the sheriff had ordered the alarm. This is a question of veracity between the sheriff and mayor. When the hose companies had arrived the sheriff made a little speech from his buggy, requesting the crowd to disperse or else the water would be thrown upon them. Before the crowd had time to disperse they were drenched with water, then the peaceable mass became furious. They did not see the fun of becoming targets for the practice of the Denver fire department. The crowd got mad. The firemen drenched them. This water business was the cause of the whole trouble.

There are quite a few items in the above paragraphs that really stand out. The writer states the events as fact, as if they witnessed it, but as no real sources were given for the timeline we are simply meant to trust the reporting. Second, the instigation of violence is squarely blamed on the Chinese party in the dispute. Historical reports about the incident are generally not so detailed as to who was actually the first to resort to violence, instead landing on more ambiguous explanations like calling it a “bar brawl,” or instead claiming it was “drunken white men” who instigated violence or began harassing the Chinese resident. It’s hard to say exactly how it began, because witness testimony was often filtered through the press, which was more often than not heavily biased and lacked fact checking processes we generally expect of media today, but it seems that the most likely explanation is that it was started by a group of white men, according to the owner of the saloon. Thirdly, the crowd of white people amassed in the Chinatown district was not seen as threatening, but “peaceable,” which begs the question: why were they gathering in Chinatown?

The crowd was sore

In the report, the crowd seems blameless – almost a victim themselves to a “feeble mayor and careless sheriff [who] had done their worst and there was no help for it.”

The restless crowd surged around waiting with a sullen temper. They had come to see what was going on, dressed in their Sunday clothes, and the mayor or somebody else had covered them with water. Therefors [sic], the crowd was sore.

In characterizing the mob as a monolith in “Sunday clothes,” the report emphasized the core of the paper’s message: the white mob was not in the wrong (at least until it was provoked into violence by the incompetent authorities, and even then the mob isn’t truly blamed). Instead, it was a mass of good Christians that stood in stark contrast to the “bawdy houses and opium dens of Chinatown” and the “much despised celestials,” and whose grievances were held to be entirely legitimate.

After the crowd were disgusted with Mayor Sopris and his water, they moved up to Holladay street, when a lively time ensued. Some boys with toy scimatars and shields cleaned out two Chinese wash-houses, the occupants of which were influenced by a fear that seemed to paralyze them. […] The crowd had, however, become somewhat smaller, at least appearances went that way. This occurred at about a quarter past three o’clock. Orders were immediately issued that lines be drawn, outside of which the crowd must remain. This was done. A heavy rope was stretched from Bailey’s corral to the lumber office on the opposite side; another from the lumber office across Wazee street to Leach & Co.’s store rooms; another was run from the rear of Bailey’s (and just beyond the lines of the Chinese quarter) across the street to Wright & Gaylord’s stables. This space had been temporarily cleared of people by the use of the hose streams, and kept the crowd away from the houses, but lately tenanted by the much despised celestials.

Tensions rose with firemen and other officials trying to quell the crowd, which was again sprayed with hoses. Then, a fireman was struck with a brick:

The excitement was intense. The people came rushing to the spot from all quarters, and in a few seconds the entire mass of humanity was concentrated on Blake street in front of the American house. The jam was terrific. There was no getting into the crowd nor out of it. The lines had been broken down, and the streets contiguous were again filled with spectators, interested parties and officers of the law. The efforts of these latter seemed unavailing. They appeared powerless to raise a finger. Reports filled the air that a fireman had been shot and killed, and that too by a Chinaman ; that the shot had proceeded from Hop Lee’s place on Blake, a little further up—near the corner of Seventeenth street. Such rumors as this, and which were countless in their number, spread from mouth to mouth, until in a few moments the crowd, spectators and all, were in a state of wild excitement.

The “gallant form” of Judge Welborn arrived at this time and reproached the crowd “in the kindly way for which the judge has ever been famous”:

The immense throng, moved to the heart, turned and started to follow the horsemen, and a moment later were marching up the street, as orderly a body of men as ever walked. A few remained, however. These were spectators, apparently, as the others had been, but they tarried to await further developments. […] The trouble was not over—that was predicted by all; everybody expressed the belief that the Chinese quarter would be surely fired before morning, and grave doubts as to the security of the Chinese themselves were entertained.

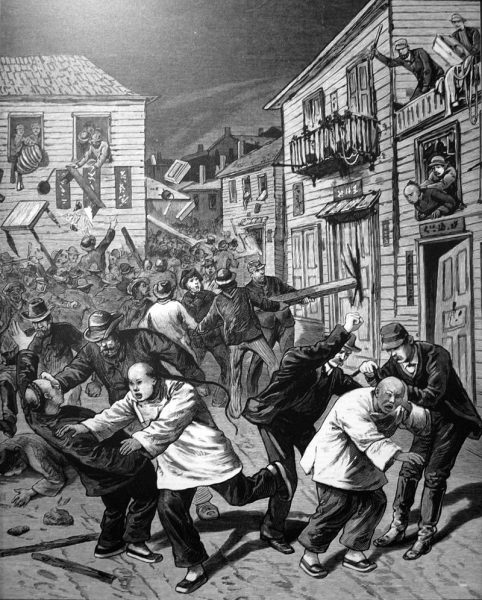

Little by little crowds returned to Wazee street and Sixteenth ; little by little the pent up fury began to find expression. Some posted themselves on Blake street, near the American house, others found places elsewhere. As the darkness increased—and it soon became very black—the fury of the crowd rose. At last the crowd opened vent. The crowd at Wazee street rushed up to the houses of the Chinese and began to batter in the doors and windows. The throng in the street grew and grew. Through the cimmerian darkness lighted for a small space only by the lamps at the streets on either side could be seen the threatening forms of men. The excitement was rising and it ran through the crowd with the rapidity of thought. The crashing of windowpanes and the sturdy blows of the leaders on the doors of the offending habitations filled the air and mingled with the angry shouts of the assembled multitude, urging them on, became a voice of thunder and its tones not to be mistaken. […]

“The Chinese must go!”

This was shouted from a thousand voices at the same time. The shout rose into a roar and the roar into a blending of fury and determination which shook the earth.

It was awful.

Pandemonium seemed to reign supreme. The attack on the doors, windows and walls was resumed. It was the fury of desperation, and the spectators recognized it, and did not attempt to interfere. Men feared to speak, for they knew not what was to come next. They waited calmly for the end[.] Occasionally the falling of a shutter or the crack of a wall sounded upon the now chilly air. It was a signal for a shout and a hurrah, and the din of a thousand voices soon became mingled with the constant hammering and battering upon the defenceless walls. At last the doors and windows were all broken, and the infuriated populace, seemingly disappointed at their inability to do further damage, attempted to set fire to the whole. Men entered the dark and deserted rooms, where the stench of opium was strong enough to knock a mule down, and gathered up the effects which had been left. No sooner did one set the example than the interior of every house in the quarter was ruthlessly entered. Then ensued a wild scene. Howls and yells went up as the clothing and household effects were hurled out through the unprotected doorways and window holes. Shirts, underwear, coats, old boots and shoes, dishes and every imaginable thing filled the air. With each successive “find” the howls of delight seemed to increase until the ear was deadened by a harsh screaming, yelling sound, as though chaos had returned and earth and sky had come together.

The damage

After attempts to quell the crowd by a general and the mayor himself, a lot of damage had already been done, and while this crowd dispersed another mob “had not been idle, nor had its efforts been unavailing”:

While the above scenes were being enacted, the houses on Sixteenth street, near Wazee and which have always been classed as a part of Chinatown, were completely demolished, so far as breakable ability extended, and there was no suspicion of anything left to the story that anything had happened. […] The washee-washee houses on Blake street, near Fourteenth, was completely cleaned out and the job was not long in its exection [sic]. Chinamen were nowhere to be seen. Their absence seemed to excite no remark.

Elsewhere, the “wash house of Hop Lee” was surrounded by a “furious crowd” who “seemed aware of the presence in the shanty of one of the execrated Asiatics.”

The victim was hauled out, the weak-voiced boys in command. He was surrounded by the crowd.

“Kill him !” they shouted.

“Hang him ! Hang him !” was heard. Officer Ryan had taken in the situation, and seeing the proceedings in the alley hastened around. In front of him was a crowd, behind him was a crowd, on either side of him there was a crowd. But Ryan’s towering form never noticed the crowd. He mowed his way through them and got to where the Chinaman was. The poor devil was being pretty badly battered up. Ryan put a stop to the proceeding without delay, and picking the Chinaman up and tucking him under his arm, walked away. He went around Seventeenth and secreted the frightened celestial in a neighboring house. The crowd followed, the boys wishing to see some further violence done and shouted excitedly. Every Chinese abode in town may be said to have been destroyed. There was one or two saved from ruin, but they were generally poor and insignificant.

Sing Hey, chased by the crowd, took refuge in an outhouse in the rear of 473 Arapahoe street, and successfully evaded pursuit for some time; but his whereabouts were eventually discovered and he was dragged out and battered up considerably. A rope was put around his neck and he was dragged about the ground, but somebody, with more humanity in his breast, counseled milder measures; Billy Frey cut the rope, and the Chinaman’s cue was cut off, when he was put into a wagon with a parting kick and sent away. He was more frightened than hurt, and turned up later as jolly as a sand boy.

About 9 o’clock last evening information reached THE NEWS that a Chinaman was in the office of Drs. Cranston and Parks, in the Moffat & Kassler block, under treatment. The report proved true. The unlucky man was found lying upon a cot in the inner or consultation room. He was unconscious and breathing heavily, with the death rattle already in his throat. His eyes were closed, the right one being much swollen, as though from the effects of a blow. Blood was issuing freely from his mouth and nose. An examination showed a face and neck much swollen, the signs of a rope being visible on the latter. The teeth had been knocked or kicked out. There was a deep wound on the top of the head, which had apparently penetrated the skull. There were bruises all over the body, from head to foot. His name was Ling Sing, and he died when the reporter was bending over him. The body was immediately removed to the coroner’s office.

Some Chinese residents were hidden in city hall and, “At 2:30 o’clock this morning about 185 Chinese, of whom nine were women, had been lodged safely in the county jail.” Then the article devolves into random notes:

The wonder is that more men were not killed. Some white men were shot by Chinamen during the melee. None seriously, however. The wounds were confined chiefly to fingers, with an occasional arm thrown in. Taken altogether it was the liveliest Sabbath Denver has seen for many a day.

[…]

It spoiled several proposed Sunday afternoon drives.

[…]

A large number of negroes were observed in the crowd which did the mischief in West Denver.

The article ends:

There were rumors afloat of a second Chinaman having been killed, but the body was not produced.

Chinatown no longer exists.

The dens of infamy on Wazee street are all in ruins.

Washee, washee is all cleaned out in Denver.

Conclusion

It is safe to say that we shouldn’t really trust much of this or any subsequent reporting on the issue, as the paper was so deeply biased on both political and racial levels, but we can take a great deal from it from a historical research perspective. The media we consume today has its roots in the mass media of the past, in this case the newspaper, which had immense power to shape the views of whole populations, as well as reflect the attitudes of the day. Delving into historical newspapers teaches us that, although journalistic standards have improved in many areas, they remain horribly outdated in other ways, especially when it comes to sticking to the truth and verifying that truth to the greatest degree possible. In other words: old news teaches us that fake news didn’t just suddenly proliferate in the 2010s.

A small but important detail reminds us of the power of fact checking. The Chinese man who was killed was not named Ling Sing, as the reporter states. His name was Look Young and he worked for the Sing Lee Laundry. Nobody was ever held accountable for his murder.

Although some Chinese people stayed to rebuild, many chose to leave the city permanently. It is thought that about 3,000 people took part in the violence, which is often referred to as a “riot.” While the violence that day surely falls under the definition of a riot, it is perhaps more to the point to liken it to terrorism, which Google defines as the unlawful use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims.

This event is one of the worst instances of racial violence Colorado has witnessed, surpassed only by the atrocity perpetrated in the Sand Creek massacre and other violence directed towards the Native American population. And like those events, so painful to remember, it should never be forgotten.

- Art Exploration Kits - April 9, 2025

- Book Club Author Suggestion: Julia Alvarez - March 18, 2025

- 20 Popular Book Club Sets - January 27, 2025