This guest post is written by Nancy Henke. Henke earned her MA in Literature from Colorado State University and taught composition and literature there for 13 years. She is now a full-time, online LIS student at the University of Iowa. You can see her work on her website or connect with her on LinkedIn.

_____________________________________________________________________

Reparative archival description is a phrase that wasn’t in my vocabulary just a few months ago. In my previous career I spent more than a decade working in higher education, but I lived in the land of literature and rhetoric, not libraries and archives, and chatted with my fellow teaching faculty about metacognition, never metadata. Now a full-time Library and Information Science student, I recently completed a practicum at Colorado State University’s Morgan Library, Digital and Archives Services (DAS) where I spearheaded a reparative metadata project. I am proud to have contributed to this crucial DEI initiative.

Reparative archival description aims to make the metadata of archives and digitized collections more inclusive. Like most cultural heritage institutions, Morgan Library’s digital collections have many objects that were archived so long ago that the language used to describe them might be racist, sexist, homophobic, or simply outdated and potentially alienating. Consider, for instance, the many photographs from the past century that describe college women as “girls,” or those that use the term “Oriental” to refer to anything Asian, or items that describe people and places as “exotic.”

Many librarians and archivists are aware such problems exist within their collections, but addressing them is a massive undertaking – one they know is worth doing but must also happen alongside the many other projects that fill the days of library staff. My practicum helped begin this process at CSU.

The first step in this work is knowing which digitized objects have potentially problematic metadata, and DAS at Morgan Library had this information thanks to the Plains to Peaks Collective, the Colorado-Wyoming Service Hub of the Digital Public Library of America. In Fall 2021 PPC’s crawlers checked the language within digitized collections against sources like Hatebase.org to flag potentially harmful items, resulting in a list of over 8700 items.

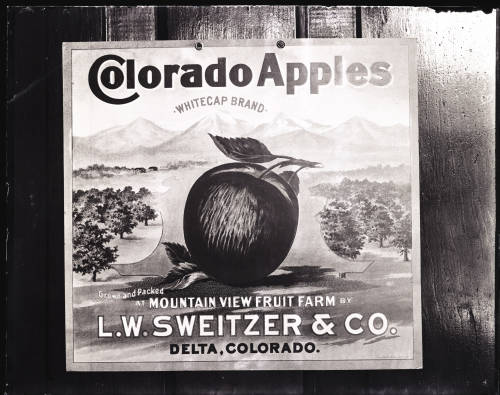

But that list was 8700+ potentially harmful descriptions, and the objects needed reviewed to identify items for further follow-up and revision. Some terms, for instance, might be used in hateful ways – like the words “fruit” or “slope” – or they might be used to simply describe images in the University Historic Photograph Collection, such as this one which is titled “Western Slope fruit.”

As you might imagine, a review of all the nearly 9000 flagged objects would have taken much longer than an academic semester, but I was able to dig through over 1500 objects – just less than 20% of the PPC list – identify those that needed further discussion and revision, summarize my findings in a report, and create a LibGuide and reading list for those who continue with the work now that my project is over.

Although each library or archive will have its own issues to contend with when reviewing their collections, there were a few trends from my project at Morgan Library that may be useful to consider.

- Of the 1500+ objects I reviewed, I identified only a small number (6.7%) that needed revision or further discussion to determine if revision is necessary. In many ways this was relieving; though some of those flagged items were highly problematic, it is heartening to know that the digital collections aren’t rife with alienating, offensive language, and a large majority of the terms are used innocuously. It is vital to remember a few things, though: first, this is true of CSU’s collections, but may not necessarily hold for every library or archive. Second, the items I identified for follow-up can only ever represent the judgement and point of view of a single person (me), and ideally a team of multiple people will scan the items I flagged and review other items on the list to ensure a variety people with varying points of view are assessing the potentially problematic metadata.

- Some of the most highly offensive language is in descriptive metadata not written by a librarian or archivist, but instead was written by the original photographer, writer of an abstract, or writer of a table of contents. This item, for instance, includes a faithful transcription of the original abstract – complete with a highly offensive term for intellectually disabled people. Any library or archives undertaking a project like this will need to determine a course of action for similar situations, especially considering that the nuances of who wrote which parts of the metadata – a librarian of today vs. photographer of 100+ years ago – are not necessarily clear to those perusing the collection. And even if it is clear who wrote what, is the explanation that “it was the photographer, not us” truly in keeping with the ethos of reparative description, which by definition seeks to repair?

- As with those who are familiar with critical cataloging initiatives, the problem at times may be with Library of Congress Subject Headings – some of which are famously outdated or offensive, and over which individual libraries have little control. This item, for instance, demonstrates just this point. Although the title and description of the photo use the phrase “small-clawed otter,” the controlled vocabulary for the LCSH subject heading is “Oriental small-clawed otter.”

I’m proud of the work I did with my practicum, and know it has a receptive audience with DAS staff who have already begun making changes and adapting workflows to ensure inclusive metadata here forward. And yet I know that this project, like so many that relate to diversity, equity, and inclusion, will never be completely “done.” It is a process of continual reflection, revision, and reassessment.

- 2025 Support for Newspaper Digitization - November 13, 2024

- An Appreciation of the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection - November 4, 2024

- “Journalism is the first rough draft of history” – Philip L. Graham - October 23, 2024